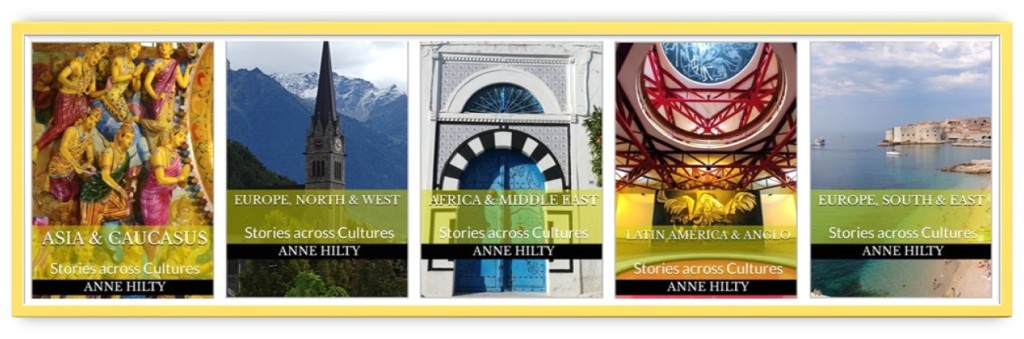

To continue reading excerpts from the Transpersonal Psy, Positive Psy, Health Psy, Personal Growth, and/or Global Citizenship series, please see the blog of EastWest Psyche (my company) or follow on social media for links. This blog will now commence with excerpts from the Stories across Cultures series.

Rwanda: Healing and Strong Women

[excerpted from, Africa & Middle East: Stories across Cultures ©2023]

Most come for the gorillas. I came to learn about genocide. And gender.

“How do you feel about your future?” I asked a young woman in her early twenties. “Are you optimistic, as a woman?”

“I can be anything I want to be,” she replied enthusiastically. “I feel no limitations now.”

The Rwandan parliament, consistently among the world’s top 10 nations for gender equality according to the WEF Global Gender Gap Index, had in 2013 elected a record-breaking 64%, the world’s first to have a female-majority at the highest level of governance; just before my late 2018 visit, that election saw 61.3% female with 55% of ministerial positions, to this date. (The 2023 parliamentary elections were delayed to 2024, to coincide with that of the president.) By comparison, the world average is a mere 25.5% for women in parliament.

“As a man,” I asked several, “how do you feel about having so many women in parliament?”

“We made a mess of things,” replied one, “so we think the women should be in charge now.”

“Let the women run the country,” said another. “We need a lot of healing, and women are the healers.”

“Our president [Paul Kagame, in office since 2000] has done a lot to bring our nation together,” according to a third man, “but it’s good to have many women working with him.”

This shift toward gender equality, though more perhaps in governance than in the average household according to various studies, is not unrelated to the profound trauma of 1994 – a civil war that saw an estimated one million people slaughtered within just a 3-month frenzy, a state-sponsored genocide in which 75% of the Tutsi people were murdered. A long time coming, it was fueled in part by earlier racist colonial practices, while pleas for international aid at the time of the violence were largely ignored.

It was just 10 years later in 2003, on the heels of a 30% national quota for same, that women took up an impressive 48% of parliamentary seats – as a conscious effort by the people for healing of their nation.

Slowly approaching the Kigali Genocide Memorial and Peace School, in walking meditation with an attitude of compassion for and honoring of the dead, I also felt deep respect for how far this nation has come in its healing. I am no stranger to societal trauma, having studied it in many areas of the world with a former clinical practice of trauma therapy. Yet I knew that the scale of this tragedy required me to prepare my own heart and mind, so that I could acknowledge their pain yet not become overwhelmed by it.

There are 250,000 souls in this place, a burial ground for many of the victims, a memorial, a place where surviving Tutsi go to visit their dead. The atmosphere is profoundly silent as any cemetery, sacred as any holy site, at once deeply sorrowful and palpably healing. There are in fact six sites of remembrance throughout the nation, and more than 250 memorials. With many educational programs and a global outreach, Rwanda has much to teach the world.

“How were you able to rebuild the peace?” I asked a specialist at the genocide center. “I know President Kigali has been a major force – but by what means?”

“Forgiveness,” he replied. “There have been prosecutions, of course, and many other efforts of healing and peacebuilding. But first, our president asked the nation to forgive one another, and to forgive themselves, for allowing such horror to occur. Never forget the dead, he told us, and never forget what happened here. But in order to move forward, to heal from the trauma, and to be one society, one people, we must find in ourselves the capacity to forgive.”

President Kigali has just announced that in the 2024 election, he will seek yet another term. It will mark 30 years since the civil war and genocide.

The peace-building efforts continue to this day. On the website for the genocide museum there is a strong message to the world: “Every community is somewhere on the path to peace – and the path to violence. Where’s yours?”

Art has also had a profound influence in the healing of a nation, a repeated theme throughout my travels. In the genocide museum itself and elsewhere, art abounds, both to speak the truth of this atrocity and to heal its wounds.

On a sign for the 2019 Ubumuntu Festival, to be held some months following my visit: “Can art heal a broken society? Art has manifested itself world over as an efficient form of communicating, expressing opinions, airing issues and sharing values about all aspects of life that affect humanity. We are convinced that art as a forum for communication, expression, reflection, innovation and creativity is a key motor for social change. The festival was first held in 2015 and happens annually following the last week of the 100 days commemoration of the 1994 genocide. It is held at the outdoor amphitheater of the Kigali Genocide Memorial Centre, free and open to everybody. 30+ countries represented, 50+ performances, 13,000+ attendees — Ubumuntu: Humanity.”

The Inema Art Center is one such endeavor. Founded in 2012 by 2 brothers, Inema is a collective of multiple artists that provides creative opportunities to underprivileged communities both as a means of expression and livelihood. They partner with other cooperatives, offer workshops and artist-in-residence programs, host a special program for orphans of the conflict, and generally strive to help Rwanda heal and grow through expressive arts.

Even so – the residue of trauma continues to this day. (How could it not?)

It’s said among scholars of post-conflict societies that resolution can take up to 5 generations. Those born after Rwanda’s 1994 travesty are too close to its trauma; often suspicious of others, they can be heard to say, “They killed us,” and similar, while government statistics show that only 5% of the population seek mental health services. The children carry the pain of their parents, whether victims of murder or survivors, and the trauma, as commonly happens, gets passed down. Often, the surviving parents have shut down emotionally or are otherwise dysfunctional, and it’s typically the eldest daughter who takes on her parents’ care.

“Do you think that forgiveness was achieved?” I asked the genocide specialist. “Or maybe partially? Or perhaps it was a good approach that was simply unachievable?”

“Oh, it helped us a lot, I’m sure,” he responded, “but we have victims and perpetrators, or their families or supporters, living side by side in many a village, and some of the perpetrators were also pardoned by the courts. Many found themselves alone with the rest of their family dead, while others have lived with severe maiming, lost limbs and more, and this is a daily reminder. I’m just not sure,” he softly concluded.

The profound terror of that period has also left its residue.

“It’s very difficult to trust anybody,” one woman told me, “Or to ever feel safe. I wake up with nightmares sometimes even now, and I struggle with anxiety. I don’t know if I’ll ever feel calm and secure again.”

Many conversations with Rwandans later, I’d had a crash course. Common themes emerged, as both achievement of yet ongoing need for: peace, respect, security – and yes, lingering feelings of insecurity, gender equality, youth engagement, entrepreneurship, self-development, master plan, fairness, justice, hope, dreams, plans, progress, pride. Rwandans focus not on the horrors of the past — though the 1994 genocide is still in the living memory of most — but on their impressive recovery thus far, and bright future. They do not forget. But they attempt to forgive, and to live in harmony.

Trauma often takes a long time to resolve. Mass trauma is another matter entirely; many people traumatized at once means that there are few who can provide solace and support. Betrayal by one’s government, the duty of which is to protect its people, and by one’s neighbors, represent an especially deep rupture of trust.

But Mama is now in charge. Many mothers and grandmothers, in fact. And while Rwanda has a ways to go for true gender equality – something which can be said of every nation – having so many women in parliament will no doubt further the healing of a deeply wounded people.

England: Counterculture by the Sea

[excerpted from, Latin America & Anglo: Stories across Cultures ©2023; edited for this format.]

Brighton. England’s counterculture by the sea.

I knew Brighton only by reputation – England’s most liberal city, its ‘gay capital’, one of those counterculture pockets that I love so well and seek out wherever I go – and with, arguably, the country’s finest weather, located as it is on the southern coast. My hometown of New York has a Brighton Beach too, in Brooklyn – a propitious sign, I thought.

On a reconnaissance mission to confirm my decision for relocation, I visited in October 2013 – and stayed in a hobbit house, complete with grass roof. As you do. The owner hosted a rather large Hallowe’en party into the wee hours of the night, to which I was invited, everyone naturally in outrageous costume. All together a very apt introduction to a quirky city such as this.

A visit to the Charleston House for the ghosts of that marvelous Bloomsbury Group of writers, artists, progressives – perfection. (In my fantasy I am one of them.) I could only dream of the Glyndebourne opera festival each summer, now convinced that southern England was the place for an art lover such as myself.

As further proof: I’d met up with musician David, whom I’d first met in Barcelona where we took a course together, and also with Mikhail, Greek immigrant to UK and international artist, whom I’d assisted in his Jeju Island project where I was then living.

A hurricane came to Brighton during my stay – also propitious, I thought: high energy, a bit chaotic, hint of danger.

On relocation to this glorious city the following June, one of my first engagements was with the Friends Society, or Quaker Meeting. In Brighton since 1658, the Friends are in many ways part of its counterculture nature, with their history of resisting authority for the sake of social justice.

I’d occasionally attended, in my early New York years, and while I’m not religious (nor, indeed, are many Friends), we shared much; the emphasis on a deeply meaningful life of purpose including service and sociopolitical activism, and the practice of group meditation with inspired sharing, were quite in keeping with my own personhood – and reflective of Brighton.

In one Sunday gathering, several expressed thoughts about Palestine, Iraq, and the causes of war consciousness, and I thought: these are my people. I was once again struck by my years spent in one of the most war-torn and deeply wounded nations, Korea, still healing from a century of repetitive trauma.

With 5 fellow members of the Couchsurfing network, I attended a concert by Gypsy Stars, a Romany family, with a parallel book launching for Refugee Radio, all part of Brighton’s effort to become a City of Sanctuary. On all accounts, indicative of Brighton’s social justice orientation.

More multicultural Brighton:

In nearby Shoreham-By-Sea, I met Quakers Gerard and Jane. He, originally American (New Jersey, no less, with a strong connection to New York), and a mental health professional like myself; she, a Brit who’d lived abroad in both Portugal and Brazil.

Also in Shoreham-By-Sea (yes, that’s its full name), was fellow Mensan Jacqui: South African, journalist and travel writer, who’d lived a decade each in Malawi and Russia, and since 1995 in England. Loved meeting other travelers who’d settled in England, particularly in Sussex – a bridge of sorts, models for my own integration. At her beach house was not only her English husband but three houseguests – from France, Germany, and Hungary.

I very soon met with fellow members of Mensa and of Business and Professional Women International, as well as friends-of-friends, and in several other avenues of connection – all in a diligent aim to integration into British, and Brighton, society. No small task, that. For successful migration, there must be both a push and a pull – a disengagement from the old, and engagement with the new.

Social media post from that time: Every day I am reminded (in, mostly, a good way) that – despite a ‘common’ language and many British cultural features in my upbringing – I am in fact living abroad, in a culture not my own. Have met several immigrants from various backgrounds, some of them here for 20-30 years already, as well as British who have lived abroad, and am now engaging in active discussion with each regarding cultural differences and assimilation / integration. (Reading some good books on the subject, too.) Phase Number Next, and Ongoing.

A friend in Tel Aviv had earlier introduced me to his cousin who was residing in Brighton, a musician who’d told me much about the vibrant local music scene. (Theatre, too. So much art to love.) In July, I was thrilled to attend the Early Music Festival – not everyone’s taste, but certainly mine.

The Brighton Bandstand, a charming 1884 Victorian Era landmark along the boardwalk overlooking the sea, was just in front of our home. At twilight one evening, as a crescent moon hung in the pastel sky, several couples were slowly dancing there to the gentle sounds of French music. On another evening the music was brightly Latin, the dance: tango.

By now, I’d begun dating not one but 2 interesting men. In Brighton, this sort of thing is not only accepted but rather expected – as evidenced by the Royal Pavilion, built in 1787, long a place for royals to meet their mistresses by the sea.

And suddenly it was Midsummer, celebrated well in this ‘pagan’ city. I was off to join an open Solstice celebration in one of the city’s parks, a large event.

Midsummer to the British, that is. On June 21st – first day of summer by any account – an English friend commented, “It’s hard to believe that summer’s half over already.” My grandmother, of English ancestry, many years ago on August 1st: “Well, summer’s over now.” (When I asked her why she said that, when it was only the midpoint of summer, she shrugged and replied, “I don’t know – it’s just what we’ve always said.”) By July 10th: 20C (68F) in Brighton, going down to 14C (57F) at night; I found myself wearing a jacket by August. A local newspaper headline read, “The night is rapidly drawing in.” And I began to understand the brevity of the English summer, even here on its southernmost shore.

One of the best pastimes during my Brighton stay was trekking with Bisou, my little dog, on Devil’s Dyke, a nearby valley managed by the National Trust. The South Downs countryside to the north of Brighton is stunning with its rolling green hills and open spaces; with that, and the sea to the south, tiny villages in both directions along the coastline – surely, what’s not to love?

Speaking of which, I took the train along the shore to Eastbourne and found a tiny, sleepy (charming, boring) version of Brighton, with a much more senior population (median age in Brighton: 38), and thought: in another 20 years or so, this might be the town for me.

In our usual late-night walk on the beach, Bisou and I came upon a group of 8 students, a mix of European and Asian, who made a great fuss over her which she naturally loved. “Are any of you from Korea?” I asked, knowing full well by appearance that at least three were – and I was right. “So is she!” I said, indicating the dog, who’d been born there. It turned out that they were from Seoul, one of my former homes, studying English in UK for the summer.

Soon thereafter, as I was sitting in yet another silent Friends meditation, my ’empty mind’ ‘waiting for Spirit’ was suddenly flooded with images of shamanist ritual – and I struggled to refrain from laughing aloud at the extreme contrast between these two forms of ‘communicating with the gods’. I missed shamans and goddesses and diving women and volcanoes. I missed Korea, but especially: Jeju Island.

From another social media post: Bisou loves our 3 (4) (5) daily seafront walks – sauntering along the boardwalk or running on the lawns, sitting on my lap as we stare out over the sea, chasing the pigeons (and contemplating the gulls) – and most of all, meeting a wide variety of people. Just now, a young Muslim mother in abaya and hijab with her two children. The boy, perhaps 3 or 4, wanted to play with Bisou but was shy; his mother, though she admitted to being frightened of dogs herself, encouraged him as she held his baby sister. “I want my children not to be afraid of anything,” she said to me, laughing softly. “My fears are more than enough.”

And another: Met two Middle Eastern kids in the park today who wanted to play with Bisou, no parents in sight. The sister, maybe 11, spoke English fairly well, translating into Arabic for her younger brother. She asked me where I’m from (apparently, I didn’t sound British) – and when I asked her in return, she replied, “Syria.” She said they live in Syria and were just visiting England. Perhaps. Or perhaps that’s what the parents told the children. I didn’t have the heart to ask her how long they’d been here.

However diverse, in this lead-up to ‘Brexit’ the UK was starting to restrict immigration, its laws and procedures rapidly changing, and I began to encounter barriers to my own attempted settlement.

I’d received a call from Jeju with a tantalizing new project on offer, and my relocation to England was soon aborted. My intended return to western culture and English language, after many years in East Asia, turned out to be a 3-month respite instead, a healthy restoration. It also served as a strong introduction to Brighton, which remains in my heart, and a lovely if shortened immersion into British culture –especially, its counterculture.

Goodbye, Brighton, for now. It’s been a pleasant summer’s interlude. Let’s meet again someday.

Colombia: Culture of Cool – and Insecurity

[excerpted from, Latin America & Anglo: Stories across Cultures ©2023]

Bogotá stirs the imagination – yet the news has not always been good.

I didn’t know what to expect. But I was surely game.

Posted to social media just prior to my March 2019 visit: Off to Bogotá today, refreshing my Spanish skills, South America – Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Brazil – the last big push of this 9-month travel in 50+ countries, just 4 flights (one 16-hour long-haul), 3 layovers, 2 airlines…. All that, plus a 13-hour time difference from Hong Kong. Two days of travel – against the sun, across the International Date Line – scheduled to arrive a mere 39 hours from takeoff at HKG. Oh, and did I mention? Bogotá is at an elevation of 2,640 m (8,660 ft). Which end is up?

This is indicative of my traveler’s life. I arrived in one piece. And I began, as I often do, with the National Museum, for a sampling of Colombian art including several by Botero, their most famous.

Una educación desde la cuna hasta la tumba / inconforme y reflexive / que nos inspire un nuebo modo de pensar / y nos incite a descubrir quiénes somos / en una sociedad que se quiera más a sí misma…. An education from the cradle to the grave / Nonconformist and reflective / That inspires us to a new way of thinking / And incites us to discover who we are / In a society that loves itself more…. [Gabriel García Márquez — Colombia’s most gifted literary son.]

Bogotá is positively filled with street art – it’s everywhere. From beauty to tragedy: One, entitled “Brutalidad Policial: Nunca Mas” with a portrait of a young man: “Querida Bogotá, Mi hijo, Nicolas Neira, tenia 15 anos cuando fue asesinado Durant las manifestaciones del 1 de Mayo del 2005 por la policia en este lugar. Ya van 13 anos de dolor luchando por la verdad y contra la impunidad.” Dear Bogotá, my son, Nicolas Neira, was 15 years old when he was murdered during the 01May 2005 demonstrations by the police at this location. It has been 13 years of pain fighting for the truth and against impunity.

All is not entirely well, it would seem, in Bogotá.

Museo Colonial was next. Spanish colonial era. Figurines in one exhibit, cute and comical, nevertheless were a depiction of the ‘casta’ system: in order of ascent, enslaved / African persons were in the lowest order, followed by the indigenous, then zambos (mixed indigenous / African), mulatos (mixed African / European), mestizos (mixed indigenous European), criollos (Spanish offspring born in Latin America), and peninsulares (Spaniards born in Spain). Reprehensible portrayal of colonialism.

And that led me next to the primary reason for Spanish conquest: Bogotá’s Museo del Oro. The Gold Museum alone is reason to come to Bogotá: pre-Columbian artifacts often shamanic in nature; one such, the famous Muisca Raft, also known as The Golden Raft of El Dorado, is exquisitely formed – and small enough to sit on the palm of one’s hand.

The major focus on the shamanic indigenous religion is because gold objects were most often used in sacred ceremony. (The conquistadors did something similar, in building churches throughout Latin America that are laden with gold.) Various depictions of the shaman can be seen in this museum, including a special installation at the time of my visit; in an immersive experience, the shamans call forth the gold, as offering to the gods. “The chant of the priests is both beginning and continuity, it has no end. Their chant journeys through time. The mamos chant to life, to the earth, to the sun, to the night, to nature, to humanity, to the universe. From the male snail and from the female snail, from the rattle and the drum, is born the ancient music.”

It’s Carnival! (Or maybe this is every Sunday in Bogotá – I couldn’t say.) I timed my visit well, though I assure you, this hadn’t crossed my radar and I didn’t know that I’d be there at the end of Carnival. In Plaza de Bolívar, the city’s main square, there were multiple military bands, street-food sellers, entertainers, and so much more, for one of my all-time favorite travel experiences. Sheer delight.

Tying in with the exhibition at the Gold Museum, this square has a long history and several names – and before the arrival of the Spanish, it was the site of the Muisca confederation of native tribes in the central Andean highlands, thought to be one of the most well-organized such of the continent.

What a remarkable city is Bogotá. But the country’s recent history, like so much of Latin America, is another story.

La Violencia began in Colombia following a 1948 political assassination and lasted to the early1960s; it then gave way to a second period of conflict, from May 1964 to the present day. The FARC [Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia] and other leftist guerrilla movements see themselves as freedom fighters for the rights of the poor and against government injustice including violence; they seek equality for all through the model of communism. The government, meanwhile, considers them terrorists and fights for order and stability, claiming the protection of citizens – while using paramilitary groups to achieve its aims. Like many such efforts throughout the region, though this is one of few still ongoing today, the governmental forces are backed notably by the US; the resisters, by Cuba.

It is the story of the 20th century throughout Latin America – yet it remains today’s news in Colombia.

The 2023 Human Rights Watch report: “Abuses by armed groups, limited access to justice, and high levels of poverty, especially among Indigenous and Afro-descendant communities, remain serious human rights concerns in Colombia.”

In yet another area of conflict: neighboring Venezuela. I would have loved to visit there as well, but it was considered highly insecure as the economic crisis was unfolding at that time, including corruption, unemployment, starvation, crime, disease, numerous politically-related killings, authoritarianism and human rights violations – and mass emigration, especially to Colombia, causing conflict along the shared border.

I was heading south instead, to Ecuador – by 24-hour bus. Even at that southern border, there was a separate and very long line for those from Venezuela, who had made it through Colombia and were seeking asylum in Ecuador.

But before reaching the border, I traveled for nearly 20 hours through the Andes Mountains, a truly remarkable experience. Just after the border and into Ecuador, I experienced my first land-crossing of the equator, thereby entering the Southern Hemisphere. (I had done so on many prior occasions – but always by airplane.) While Bogotá at 2,640m (8,661ft) is the world’s 4th-highest capital, Quito is even higher at 2,850m (9,350ft); good news is, though the region is at risk for mosquito-borne illnesses such as malaria and Zika … mosquitos can’t live above 2,200m.

Despite its longstanding conflict and other security issues, Colombia exceeded all my expectations – and I quickly learned to love Bogotá.

Bulgaria: Traces of Thrace

[excerpted from, Europe, South & East: Stories across Cultures ©2023]

I first saw kukeri not in Bulgaria – but in Greece.

Thessaloniki, to be exact, in February 2017, and where, in the 1890 census, Bulgarians made up 8% of the population – Greeks, just 14%. (Part of the Ottoman Empire with Saloniki its ‘second capital’, the city was 22% Turkish – and 49% Jewish, expelled from Spain some 5 centuries prior and welcomed into the Ottoman sultanate – but that’s another story.)

Today the Bulgarian community in Saloniki is much smaller, but in late winter, the kukeri dance. Wearing exaggerated animal-like masks, they scare the last ‘evil’ of winter away, so that spring can fully arrive. And in that unexpected moment, as they danced along the waterfront cheered on by many others of their community in traditional dress, I became especially intrigued by Bulgaria.

In August 2018 as part of a wider exploration of the Balkan region and former Ottoman Empire, I arrived in Sofia – by bus from Romania, taking in the stunning countryside along the way.

In fact, it’s widely thought that the kukeri tradition, found in other Balkan cultures, came from pre-Christian Thrace – today northeastern Greece (though not as far west as Thessaloniki, which is Macedonian instead – yet another story later to be told), northwestern Türkiye (much preceding the Turks), and southern Bulgaria. What’s most apparent: there has long been cultural communication throughout this region.

Thrace is also the influence behind the anastenaria, traditional fire dancing found throughout the former Thracian region, as well as Bulgaria’s unique folk music, a form of polyphony. The fire dancing, an ecstatic form of worship now to patron saints including konaki or special shrines, is an annual event held in late May – that gives every appearance of pre-Christian Thracian traditions.

Bulgarian polyphony, long a musical passion of mine, weaves 2 distinct melodies over one another. Akin to mystery and magic, described as ‘beyond the notes’, modern jazz has nothing on this. It is perhaps also an indirect influence on the plethora of renowned opera singers this country has produced; clearly, music is highly valued.

Long a regional center of culture and education, Bulgaria has a complex history of multiple influences, in fact – and a tapestry of culture as a result. The city’s monument to Saint Sophia, after whom the city was named, was a pre-Christian Hellenistic concept of wisdom (‘philosophia’ as love of same, per Plato) that, in both Orthodoxy and Catholicism, has been perceived as divine – and personified as female.

Many Roman ruins have also been uncovered, unsurprising considering that Constantinople in Eastern Thrace, today’s Istanbul, served as the Eastern Roman Empire for well over a millennium. Beneath Sofia, the Serdika Roman fortress ruins are on public display.

My visit to Sofia was well informed by meetings with BPW colleagues and by explorations in the National Gallery of Art, housed by a beautiful former palace, and in the city’s other National Gallery (yes, two). Folk culture of Bulgaria was well depicted in the city’s Ethnography Museum. Its cathedral is iconic, and speaks to the long influence of Orthodoxy in this culture – while the Grand Mosque, and Grand Mufti administrative office for all Muslim-related matters, remain as evidence of its long governance by the Ottoman Empire, though most of the earlier Turkish population migrated to the new republic.

Hearkening back to that late-19th century large Jewish population in Thessaloniki, along with a substantial minority of Bulgarians, local lore has it that mid-20th century Bulgaria, not occupied but an ally of Nazi Germany, refused to give up their Jewish citizens to German forces; while the government was pro-Nazi and deportation of Jews was scheduled, the citizens resisted and all 43,000 were rescued.

Or — were they? Controversial, as while they were not sent to death camps, they were nevertheless strongly discriminated against by their government, including crippling economic restrictions. Further, Germany ‘awarded’ Macedonia and Thrace to Bulgaria as territories — where the Bulgarian government deported 7,300 Jews from the former and 4,000 from the latter to the Treblinka camp in Poland, from which almost none returned.

As with all European cultures, the layers of Bulgaria are deep, many, and complex.